(OKINAWA SHORIN-RYU SHIZOKU)

Philippines Karate Club

Welcome

to our home page. Here we will feature

latest news in and about our organizations' activities, locally and internationally.

We will also feature in a column about extras: Seminars, Upcoming Tournaments, etc.

You can also send any news item, photos, greetings for web publishing to : horizonryukai@hotmail.com.

We encourage your contributions, whatever it may be, comments or suggestions regarding your chapters

training courses and schedules.

Featured Article

From Classical Fighting Arts #9

Why bunkai? Many seniors of “traditional” karate styles in Hawaii had their start in Kenpo (for example, Bobby Lowe, Paul Yamaguchi, Masaichi Oshiro, Tommy Morita, Jimmy Mivaji, Kenneth Funakoshi, and former Chief of Police Lee Donohue). I also studied Kenpo Karate in high school and taught it while in college. Kenpo is a great art and is interesting because it is not kata based.

While kata are taught in Kenpo today, the earliest classes here in Hawaii, starting with Masayoshi James Mitose and then with Thomas Young and William Chow, were technique based. The only kata originally taught was Naihanchi Shodan (sometimes referred to as the “Monkey Dance:’ perhaps referring to Choki Motobu).

Like the early jujutsu classes taught by Danzan Ryu founder Henry Seishiro Okazaki, Kenpo students would learn sets of defenses against certain attacks: ten sets against a grab, ten sets against a punch, ten sets against a club, ten sets against a knife, and so on. A fair amount of cross training took place between Mitose’s and Okazaki’s students. Kenpo movements were classified by the attack. When someone grabbed you, you knew what to do because you had practiced a certain grab set thousands of times.

The same is not true of ordinary kata based karate. After a few years 0f training, most karate students will “know” several kata. Of course, there is a world of difference between being able to merely perform the movements 0f the kata and truly understanding them. You will not know what to do, more importantly, your body will not know what to do instinctively, unless you break down and break out the movements into something you can practice with a partner. Bunkai literally means to “separate”, bun or “break down” and kai “understand.” Kata bunkai means to break down the movements of the kata and study their practical applications.

Is bunkai really necessary? So what if you never learned bunkai? Don’t feel bad, you’re not alone. If you study karate simply to get in shape or perform kata in tournaments, bunkai seem like a waste of time. What counts to competition is looking good as defined by the rules particularly to the judges and the crowd.

By the same token, bunkai is not really necessary for students interested solely in kumite. Why? Because only the most basic applications are permitted in kumite. I once read a booklet for a tournament held here in Hawaii. It listed techniques not permitted in kumite competition—things like pulling hair, poking eyes, twisting joints, choking, throwing, kicking the groin, etc. They were all the best techniques!

So kumite with rules limits the fight, and kata without bunkai has no use for a fight at all. And if you can only kick, punch, and block, karate offers very little advantage. A larger and stronger person can probably kick, punch, and block harder, even without martial arts training. Only through a proper study of bunkai can kata actually be used for self-defense. This gets us back to the originators of the kata. They included techniques that worked for them. You will have to practice techniques so that they will work for you. Bunkai cannot be a mere mental process 0f identifying applications. Mental bunkai won’t work in the real world.

Before 1900, karate was taught in private, usually to only one, two, or a handful of students. Even great teachers like Anko Itosu had relatively few students. These were “private” students who often trained with a teacher flat life. Such students, after learning the movements and sequence of kata, also learned the meanings. The term “bunkai” might not have been used. The study of applications was an essential part of the process of learning kata. An emphasis on bunkai as a distinct subject only became necessary when the study of applications was watered down or eliminated altogether.

When karate was taught was in public, first in the public schools in Okinawa and later in colleges and schools on mainland Japan, teachers suddenly had to deal with large groups. Instead of training with a teacher for life, students trained for only a few years, or even only a single term. In such a short tune, teachers could only teach the most basic form of karate. And without personally knowing each student (and his family) for many years, a teacher might be reluctant to teach certain dangerous applications or techniques.

It should not be surprising that private students (those who trained at the teacher’s house or even at the family tomb) and public students (those who generally trained at schools) would be taught differently. Now rake this forward a few generations. Soon, whole generations of students would learn karate without studying applications—and then they would become the teachers!

Bunkai General Ideas

It is not possible to describe actual kata applications in this article, nor would it be proper to do so. The print medium means that I don’t know you personally and can’t vouch for your character. Moreover, my knowledge is limited to what I know at my stage of training. But, here are ten general ideas about bunkai that might be helpful to beginners.

Lost in Translation

Kata are sequences of techniques, presumably ones the creator (or modifiers) 0f the kata had found to be particularly effective. Today we know the names of the kata and the names of each technique and stance present in the kata. Fukyugata Ichi (created by Matsubayashi-Ryu founder Shoshin Nagamine in 1940), for example, begins with a gtdv1 barai or gedan uke (left downward block) in a left zenkutsu dachi, (forward stance), followed by a chudan tsuki (right middle punch) in a right shizentai darhi (natural stance), Can you visualize this?

That was a trick question! Once the movements of a kata are identified as specific techniques, the meanings become fixed. A “block” has a certain meaning, as does a “punch!’ A stance has a certain configuration and weight distribution. A dynamic process is reduced to a series of still photographs.

We assume that techniques and movements have always had names. The teachers 0f old were much less likely to realize or write down such things. They would demonstrate techniques and say “like this!’ The student would follow and generally not ask any questions. If the student asked for clarification, the teacher would often reply “1 already said, like this!’ The teacher was unlikely to elaborate verbally.

Words became particularly necessary when books about karate started to be written in the 1920s. Each technique had to be named to accompany the proper picture or photograph. Often names were just descriptive made up. If the teacher showed a punch to the face, the author (in his language) might have used the term “face punch!’ Or he might have used “upper level punch” or “rising punch!’ But the odds are that his teacher used no term at all (except ‘like this!’).

But wait a minute. Suppose instead of merely punching, the teacher actually poked the attacker in the eyes, dosed his fingers, and followed through with a punch. Should this be written down? Perhaps the author of the book would leave out the eye poke because it was not quite suitable for the general readership. After all, we can’t have children going around poking eyes. Such a gruesome technique might offend the publisher, who probably thought that Kendo was a more noble art. Karate teachers had to overcome widespread prejudice against and misinformation about their art during this period. Besides, this aspect of the technique could be practiced by the teacher’s advanced students, who didn’t really need a book anyway.

Editorial choices aside, the very act of naming techniques presents a very real danger of limiting them in terms of performance and applications. My sensei, Katsuhiko Shinzato, is a professor of linguistics in Okinawa. Although fluent in both Japanese and English and an established expert linguistics, he resists any requests to label techniques or dynamic body processes. “In order for the body to move freely” he says, “the mind must not be fixed.” Once you name a technique, you limit it—you limit its performance and potential applications.

Concealed Meanings

This follows from the previous section. Think back to the eye poke/face punch. Privately the teacher might show this. In public, he might only show the punch, and then it might be to the chest, so as not to look too brutal. His dose students would understand what he did, but the public would come away with a shallow understanding of the move. How the teacher performed the kata often depended on who was watching. This is not mere speculation. Many movements in kata—the ones we have today—are the watered down, public versions. Take the Pinan kata, for example. These kata were specifically designed or altered from earlier kata for public consumption. The same is true of Fukyugata Ichi. Even older kata were sanitized. Open hand techniques were replaced with punches. Toe kicks were replaced with kicks using the ball of the foot. Assume for a moment that I am correct. If we inherited watered-down kata, what kind 0f bunkai will we practice? A punch to the chest or face may not be as effective as a simple poke to the eyes. We will consider how to handle this later in this article.

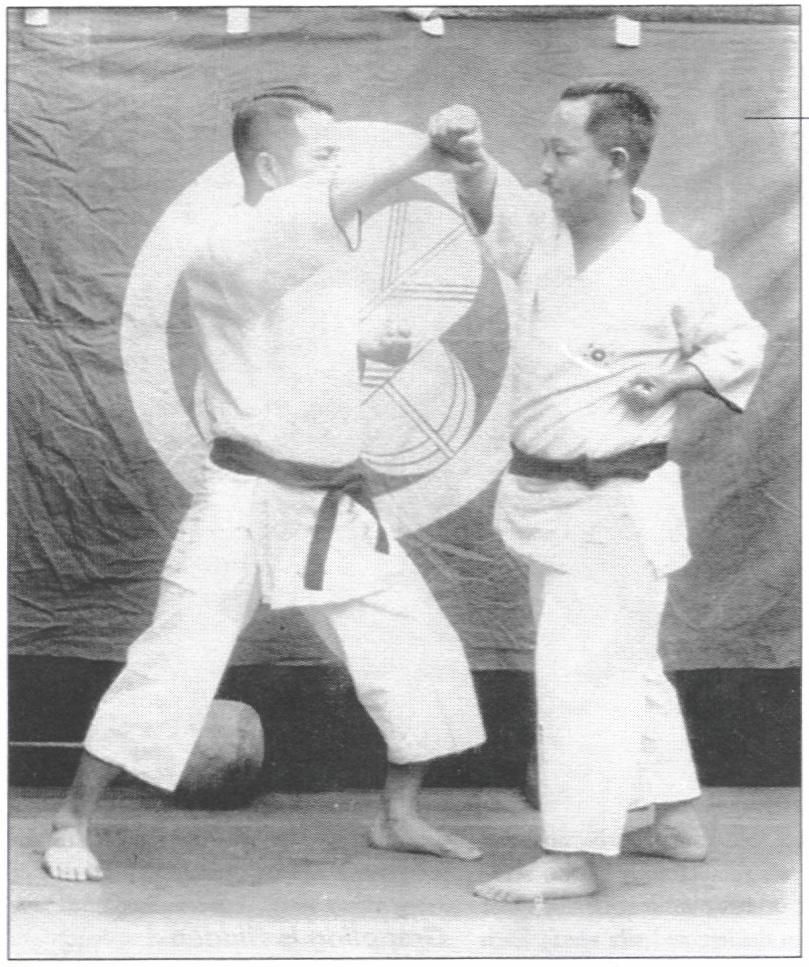

Grappling

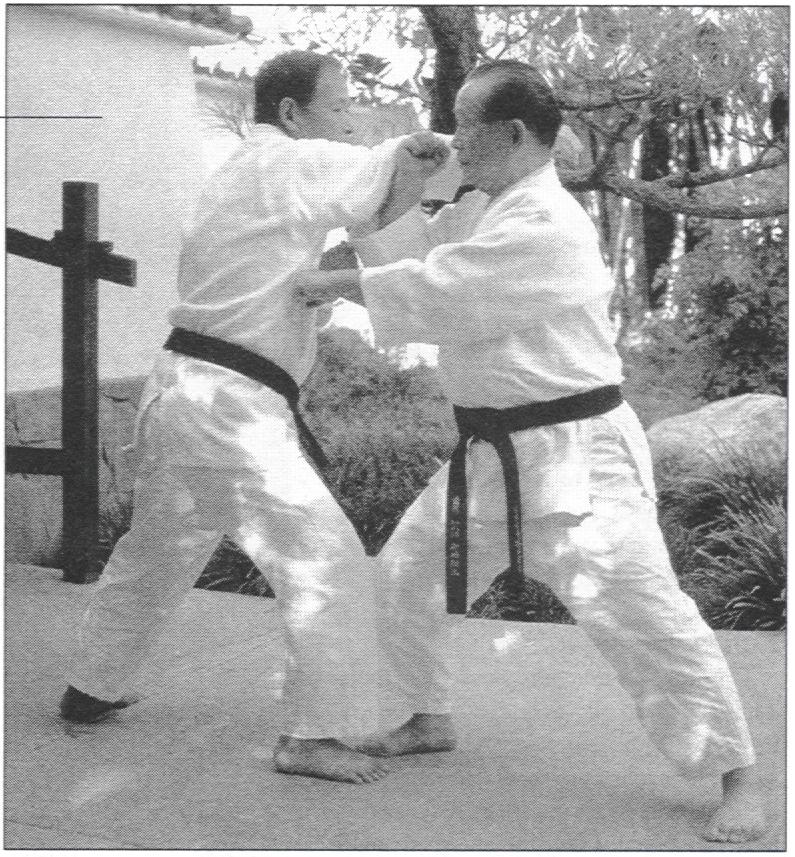

Here is where it gets really interesting. When the movements of kata were made public the first thing to go was the grappling element. This seems to be particularly true m Shorin-Ryu based systems. Goju-Ryu evolved later and grappling seems not to have been suppressed in the kata. However, in many systems joint manipulation and grappling techniques were either eliminated or changed into blocks. Thus, a block might not only also be a punch; it might also be a joint lock or throw. in fact, for many karate teachers, these are the more likely applications. But if you execute a block with the body dynamics for a block, it might not work properly as a throw. Blocks work by stopping or redirecting an attack. Throws involve a completely different process of intercepting and redirecting the attacker’s momentum. You have to know whether you are blocking or throwing in order to do it properly.

When Kentsu Yabu came to Hawaii he was asked what the difference was between karate (which then meant “China Hand”) and jujutsu. His reply was remarkable. Think about jujutsu for a moment. Its curriculum is vast. Yabu answered that jujutsu was only 10% of karate. This was more than an idle boast. We know today that pre-public school system karate had a comprehensive grappling element, often called tesumi or tuite. In other words, an old school karateka could punch like a boxer, throw like a judoka and manipulate joints like a jujutsu expert. If you ask me, the closest art to karate is old style aikido. If Yabu Sensei was right, a karate expert should know just about every aikido technique. Do you? More importantly in the context of this article, when you analyze the movements of a kata do you recognize the aikido, Judo and jujutsu-like elements?

It All Counts

Many of us have studied other martial arts. After many years or decades of karate practice, the similarity of techniques from other arts becomes apparent. We start to see how a certain movement in a kata might be like certain Judo throws how another might be like an aikido joint locks, etc. I use the word “like” because it is important to keep m mind that the rules governing or shaping other arts might not apply to karate. Judo has become a sport. Judo throws are designed not to Injure. Karate throws would be useless if the attacker could simply get up and resume the attack. One of the karate seniors here in Hawaii demonstrated a take- down on me. Without warning he seized the muscle on the left side of my neck and with his other hand grabbed my right ear. With a little twist I was writhing in pain and ready to go in any direction he pleased. I don’t think this would be allowed in Judo and I don’t remember such a technique in aikido. But it certainly worked.

Yakusoku Kumite

You might be wondering how yakusoku (promise or prearranged) kumite fits into this analysis. Bunkai can be easily adapted into drills of two man sets. That’s the idea, and perhaps that’s where the kata came from in the first place (a compilation of two man sets with the partner removed). Remember the Kenpo arts. For each attack there is a set of responses. Karate researcher and writer Patrick McCarthy is a strong advocate of two man sets training, which he calls renzokugeiku. He has theorized that early kata represented the culmination of what the student bad already learned (basics and two man sets) rather than being the primary vehicle for teaching such techniques.

The utility of these two man sets depends on your system. Some schools practice yakusoku kumite forms that are little more than simple blocking drills. Such yakusoku kumite approximates only the most basic level of bunkai.

You might be wondering how yakusoku (promise or prearranged) kumite fits into this analysis. Bunkai can be easily adapted into drills of two man sets. That’s the idea, and perhaps that’s where the kata came from in the first place (a compilation of two man sets with the partner removed). Remember the Kenpo arts. For each attack there is a set of responses. Karate researcher and writer Patrick McCarthy is a strong advocate of two man sets training, which he calls renzokugeiku. He has theorized that early kata represented the culmination of what the student bad already learned (basics and two man sets) rather than being the primary vehicle for teaching such techniques.

The utility of these two man sets depends on your system. Some schools practice yakusoku kumite forms that are little more than simple blocking drills. Such yakusoku kumite approximates only the most basic level of bunkai.

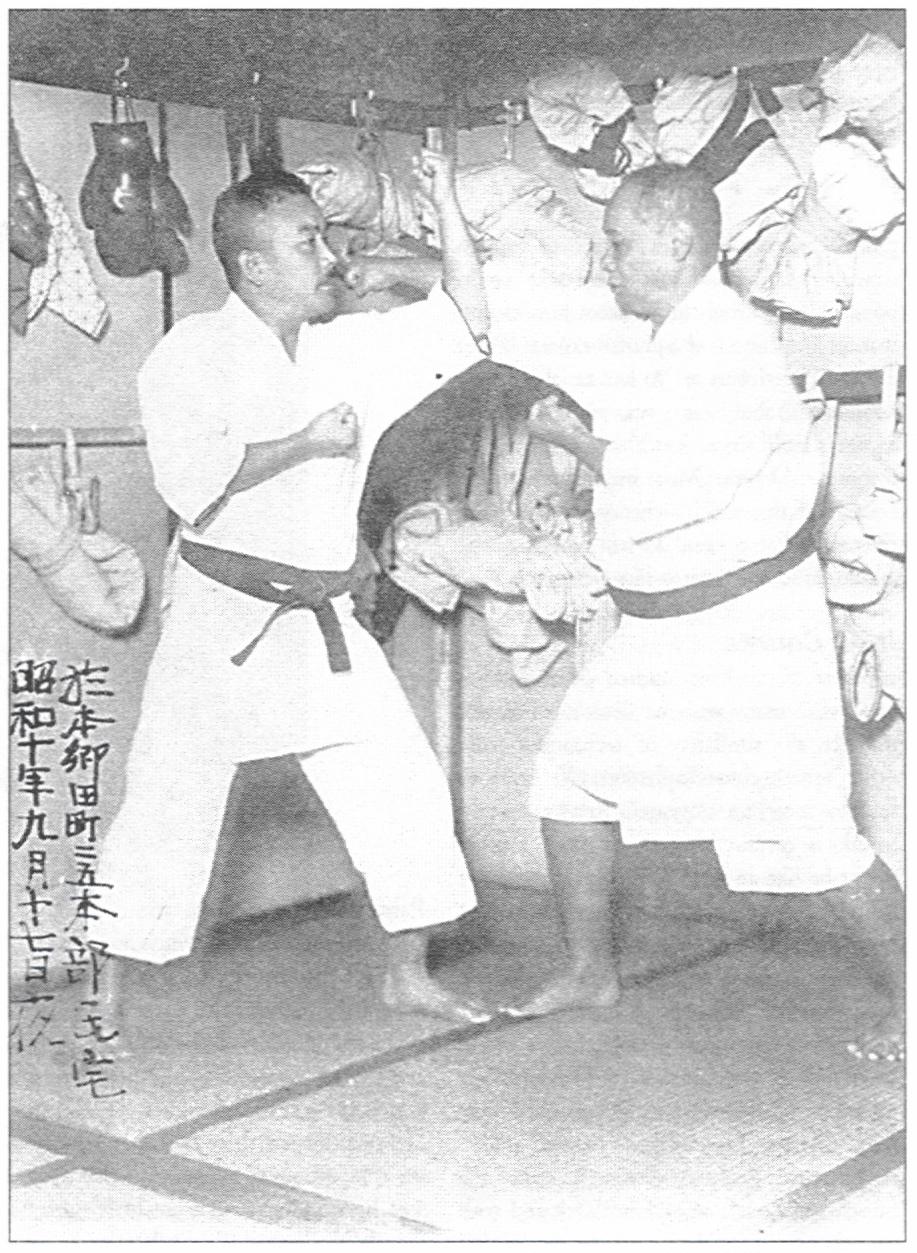

I practiced a form of Shorin-Ryu with IS kata and only 7 formal yukusoku kumite forms. These yakusoku kumite forms were more for demonstration than kata analysis. With 18 kata, the number of potential two man sets or paired drills that bunkai analysis could reveal is virtually unlimited. Thus, a handful of yukusoku kumite, while helpful, is not the same thing as bunkai. One of the earliest sets 0f yakusoku kumite-type forms are the Motobu Choki Juni Hon Kumite. These are twelve patterns developed by Choki Motobu and still taught by his son, Chosei Motobu, and others. They appear in Choki Motobu’s two books, Okinawa Kenpo Thudi Jutsu Ku,,, ire-Hen, published on 5 May 1926 by Rvukvu Karate-Do Shihan Kai, and Witashi no Karate Jutsu (My Karate Art), published in 1932.

The Motobu sets are interesting because they are based on older kata such as Naihanchi and Passai, as opposed to the modern Pinan, and because they reflect Motobu’s expertise as a fighter. If the 12 sets are practiced on the right and left sides and with different attacks, they form an excellent reference source for use in bunkai analysis.

A Punch is a Block;

A Block is a Punch

You have probably heard this saying. A punch can al5o be a bl0&. A block can al50 be a punch (or a strike). This is true m a basic mechanical sense. If someone punches toward your face, you can block it by punching toward his or her face. Your punch will intercept the attacker’s arm, thus blocking it.

Each Movement Has Many Meanings

In a larger sense, a punch can be much more than a block. The same is true of a block. Almost any technique can be used m a variety of ways. Rick Clark wrote a book entitled 75 Down Blocks: R4inin Karat, Technique. If a simple down block can have at least 75 meanings. How many meanings can be found in a kata consisting of many different techniques?

One Inch. Five Meanings

My first teacher of karate (Kenpo Karate) was Florentino S. Pancipanci. He also taught taijiquan and gung fu (as well as escrima, which I did not learn). He used to say that for each inch 0f movement in a kata, there were at least S meanings. That’s right—I said each inch. And he would demonstrate this.

“Dirty” Techniques

My good friend, Professor Feliciano “Kimo” Ferreira teaches Kempo. He often talks about “dirty” techniques. I wince just thinking about it, but I’ll describe just part of one here. The end of this particular technique involves ramming the attacker into a wall (or other hard object) and raking his face against it as you take him down to the ground, where you proceed to “stomp the cockroach juice out of him:’ I’m not kidding and most of the techniques he describes are far worse than this.

Finding Bunkai

Naturally the first place to start is your teacher and seniors. Assuming that you are the teacher or are on your own, where should you look? I mentioned Kenpo above. W can learn a lot from Kenpo and other arts. I often say that if you want to learn the bunkai 0f traditional karate kata, observe Kenpo applications. Professor Ferreira is a virtual walking bunkai encyclopedia.

Many fine teachers have produced videos or DVDs showing various bunkai. I will mention just four whom I have personally found to be very interesting (in alphabetical order): Feliciano Ferreira, Mono Higaonna, Patrick McCarthy and Yang Jwing-Ming. I mention them because their tapes are filled with applications and/or drills. You may know of others. Also, each of the above teachers is from an art that differs from mine. I practice the Kishaba Juku form of Shorin-Ryu. It is eye opening to see applications from Kempo (Ferreira), Gou-Ryu (Higaonna), Koryu Uchinadi (McCarthy), and Chinese arts (Jwing-Ming). I always say that if someone can do something better than I can. I want to learn it or at least understand it in case it is used against me. You can’t counter what you don’t know.

Bunkai: Analysis and Construction

Here are some guidelines I use when applying bunkai analysis to the kata I practice. Some teachers will disagree with them, arguing that the techniques of a kata are literal and fixed. While I respect this interpretation, I personally find it to be too stiffling.

Movements are Done Close

The maai (engagement distance) in Okinawan karate is very close—your elbow should be able to touch your opponent. At that range, bunkai is unlimited. You can hit with any part of your body, apply joint techniques, stomp, trip, and throw. If you are outside of that range, perhaps you should try to escape. The next time you are in a crowded elevator, ask yourself what techniques would work.

Range of Movement

Each movement in a kata represents a potential range of movement, not just a single movement. A middle punch includes all heights (lower, middle, upper and all points in between). A middle block includes all blocks that can be executed with the same body dynamics.

Symmetry

Many kata are asymmetric and contain movements done only on one (right or left) side. The makite-uke (winding block) sequences in many Matsubavashi-Ryu kata (Wankan, Wanshu, Rohai, and Passai) are good examples of this, as they are only done on the right side. Bunkai should be practiced on both sides.

Few Movements

Bunkai can apply to a single movement or a combination of movements. When the combination becomes too lengthy, the application tends to become rigid and dependent on an extremely cooperative partner. It might look impressive to demonstrate a long combination but m a real situation your response will likely be short and to the point. Combinations normally follow the sequence 0f the kata. However, combinations can be practiced out of sequence and even assembled from different kata.

Double Movements

Simultaneous double movements should be practiced together separately; and sequentially. Think about a wari uke (double middle block) as found toward the end in Pinan Godan. These blocks could be analyzed together as two simultaneous blocks, separately (tight or left), or sequentially (first the right, then the left, and vice versa). Each block, representing a range of movements could be practiced as upper middle, or lower (and all points in between). In addition, since a block can be a punch or strike, these variations should also be practiced.

Multiple Attacks

Imagine that the attacker punches with the right. Apply your analysis. Now he punches with the left. Apply again. Now imagine that he grabs your collar. Apply again. Now he stabs. Get the idea? The attack is not fixed. Your response is not fixed.

Empty Movements

Don’t leave the attacker standing. Imagine that the attacker punches. Don’t simply block and then turn to face the next attacker. Movements typically do damage. Consider the first movement of Pinan Yondan. If it is merely a block (double), what happens when you turn for the second movement? The first attacker is still there! But if the first movement is a combined block and strike, or if it is a grappling movement that flows into the second movement, then the bunkai makes more sense.

Grappling is Hidden

Many striking techniques work better when a joint lock or throw is applied first. The throw or joint lock may be hidden (represented as a standard block) or even eliminated in the kata. Look for throws when a high block is followed by a low block and vice versa. Stepping movements are often trips.

Some Double Blocks are Arm Bars or Wrenches

Many techniques, especially those involving double blocks like morote uke, and all forms of shuto, can be interpreted as arm bars or wrenches, applying pressure to snap the attacker’s arm, leg or even neck.

Two Hands Together

Your two hands should work together. There is a saying that your hands should be like man and woman. When your hands are together (or close), look for the grappling element, especially when an open hand is near a closed hand. In the starting position of kata, imagine that you have already applied a joint lock. This works especially well in the Naihanchi series. Don’t bring your hand back empty. In many karate styles, the opposite hand is pulled back during a punch. One interpretation is that the returning arm (or elbow) may be used to strike someone grabbing from behind. However, it is far more likely that the hikite (returning hand) will be pulling or twisting something like the attacker’s arm, hair or groin. When you punch with two hands simultaneously, the hand closer to your body is probably a grab seizing the attacker’s punch. The last movement of Naihanchi Shodan is a good example of this. Grabs are often represented as punches. When you block with one hand, your other hand often parries or checks the attack first. If the parry or check is successful, the blocks can instantly change into an effective strike.

More Than Seiken

There are many ways to transmit power with the hands. If your kata only uses seiken (punching with the knuckles), try using other forms (one knuckle, two knuckles, knuckle of the forefinger, knuckles of the fingers, fingertips, etc.) The type of fist or other part of the hand used depends on the anatomical structure that you are striking.

More Than Chusoku

Similarly there are many more ways to kick than with the - chusoku (bail of the foot). Old style kicks were often done as tsumasaki geri (with the tips of the toes) in a grabbing manner. Kicks were also done with the large knuckle on the side 0f the base of the big roe, side of the foot, and heel. A kick to the groin would utilize the instep. The knee could also be used. Do not limit your kicks.

Kick Whenever Appropriate

Kata generally contain few kicks. That doesn’t mean that you should only kick when one is present in the sequence. Kick whenever appropriate, particularly when you have seized the attacker. Remember that a kick represents a range of movement rather than a single technique.

Low Kicks

Old style karate only used low kicks—generally below the waist. There is a saying that if you want to kick someone in the head, you should throw him to the ground first. If you kick high the attacker could kick you in the groin or supporting leg. It also makes you vulnerable to grappling techniques.

Target the Feet

Karate techniques are applied on multiple levels (jo, chu, ge) simultaneously Don’t forget to step on the attacker’s feet, twist his legs, strike his knees, etc Leg pins, stomps and sweeps are widely present m the Naihanchi series of kata. Again, these techniques work best when you are very dose to the attacker.

Uraken

Use the uraken, (back fist) in connection with other movements. A back fist can easily follow a punch, block or elbow strike.

Natural Sequence

There are certain natural sequences such as punch, elbow strike, shoulder strike, uraken. These four techniques can be “thrown” as a single movement. With one movement, you strike multiple times.

Block, Strike, Manipulate, Throw, Get Away

There are also phases to applications. At the end, the attacker should probably be on the ground or writhing in pain. You should be getting away or ready for the next attacker.

Simple is Better

Don’t become enamored of complicated bunkai. Simpler is faster and less likely to go wrong. The simplest techniques are strikes. That is why teachers who strike well often don’t emphasize grappling.

Everything Looks Good When Prearranged

It’s easy to defend against a prearranged attack. Demonstrations always look perfect. Bunkai helps you to prepare for an unexpected or a changed attack. It is one thing to learn vocabulary words: it is another to be able to freely converse.

Connecting the Movements

Once you practice bunkai, you will see how the movements within a kata connect to each other, and how they connect to movements in other kata. Kata are useful tools, not sacred formula.

Dead Body

Bunkai makes you realize what you can do at any point in the kata. Any dead spaces, or places where you cannot easily move, will become obvious. Avoid shinitai (having a dead body). You should 5e able to move and transmit power freely, In any direction, at all times.

Don’t Forget Body Dynamics

Karate requires extraordinary movement. With proper body dynamics, we can move quickly and generate and transfer maximum power, all with minimal effort. Only then can we actually use the applications we have learned through bunkai analysis. Kata training can help us to develop extraordinary movement.

Don’t Be Limited

The idea is to free your movements, not restrict them. Even lists like this can be a hindrance. Keep an open mind. Bunkai runs the gamut from the simple to the complex.

Sometimes a punch is just a punch. Sometimes the actual application may appear to be hidden But there really are no secrets in karate. Once you understand the technique, the meanings are plain to see. Teachers have a right and responsibility to teach what is appropriate to each student at his or her level of training, but it is wrong to characterize techniques as secrets. There are simply bunkai you know and bunkai you don’t know yet

Toshihiro Oshiro was visiting Hawaii and came to my house. The subject turned to bunkai. It was obvious that Oshiro Sensei’s knowledge of bunkai (not to mention body dynamics) was vast. At one point (I am paraphrasing), he mentioned that he sometimes woke up thinking about bunkai. He looked very serious when he said this.

When you study bunkai, you will see applications everywhere. Just ask my children. I am always asking them to punch or grab me so that I can try out an application that just materialized in my mind. I am confident that I am not alone in having had many dreams about bunkai. One thing I have had to avoid is thinking about bunkai while driving. I hope that you’ve enjoyed this introductory article. You’ve read almost 5,000 words. Just imagine if you didn’t know what any of them meant. Kata without bunkai is like words without meaning. Bunkai transforms kata practice and opens a window to a fascinating world. I hope you will enjoy reading your kata!

Charles C Goodin is the chief instructor of the Hikari Dojo and the head of the Hawaii Karate Seinenkai and Hawaii Karate Museum (hikari.us). He is a member of the Hawaii Karate Kodanshakai (hawaiikodanshakai.com). He teaches the Kishaba Juku form of Shorin-Ryu and Yamani-Ryu Bojutsu.

|